At Commonwealth Contractors, our approach to building mirrors my personal philosophy on life, blending practicality with a touch of ingenuity. With a deep respect for classical building principles and a keen eye for modern improvements, you can rest assured that when you collaborate with Commonwealth Contractors, your project will be managed with quality and integrity.

The first homes in Virginia were built out of necessity, but they were also built with heart. They wanted a place that felt safe, where family could grow and gather. Centuries later, this intention remains the foundation of every home we create.

.svg)

Colonial architecture in Virginia is the story of adaptation, resourcefulness, and survival in the early 1600s through the first decades of the 1700s. The buildings of this era were shaped by the backgrounds of their builders, the materials at hand, and the demands of a new and often harsh environment. Unlike the more refined and classically inspired Georgian buildings that would follow, Virginia’s colonial homes and structures were practical, vernacular, and deeply tied to the land and society that produced them. This article explores who settled colonial Virginia, how and where they built, the distinctive features of their architecture, and why so few original examples remain today.

In the heart of Charlottesville, VA, Commonwealth Contractors are established experts in restoring, renovating, and building homes that honor Virginia’s colonial architectural heritage. If you have any questions after reading this guide, please reach out.

Who Settled Colonial Virginia and Where Did They Build?

English Colonists and the Tidewater Frontier

The first permanent English settlement in North America was established at Jamestown in 1607. The earliest colonists were overwhelmingly English, sent by the Virginia Company of London, and included a mix of gentlemen, laborers, craftsmen, and indentured servants. The initial groups were all male, but by 1619, women began arriving to help establish more permanent family-based communities.

Settlements clustered along the navigable rivers of the Tidewater region, such as the James, York, and Rappahannock, where transportation, trade, and fertile land for tobacco cultivation were readily available. As the colony grew, settlers pushed inland into the Piedmont and, later, the Shenandoah Valley. In these new frontiers, they encountered and sometimes clashed with Native American tribes, as well as German and Scots-Irish pioneers who brought their own building traditions.

Motivations, Social Structure, and Labor

The primary motivation for settlement was economic: the pursuit of wealth through tobacco and other cash crops. The plantation system and the institution of slavery evolved rapidly, with enslaved Africans arriving as early as 1619. Most colonists, however, lived in modest circumstances, building simple homes with the help of family, neighbors, indentured servants, and enslaved laborers. Most homes were built quickly and cheaply, with little expectation of lasting more than a generation, driven by the need to move as tobacco exhausted the soil.

Materials and Building Techniques: Making Do in a New World

Abundant Timber and Earthfast Construction

Virginia’s vast forests provided an abundance of timber, which became the primary building material for early colonial structures. The most common construction method was “earthfast” or “post-in-ground” building, where large wooden posts were set directly into the earth to form the framework of a house. This technique was fast, required minimal tools or skilled labor, and was ideal for a society on the move.

Walls were typically filled with wattle and daub (woven sticks covered with clay or mud), or clad in rough-hewn planks. Roofs were covered with wooden shingles or thatch, and floors were often packed earth or simple wooden boards. Brick was rare and reserved for the wealthiest colonists or for chimneys, as it required skilled labor and kilns. The use of stone was more common in the western regions, especially among German settlers in the Shenandoah Valley.

Community and Labor

Building a home was a communal effort. Neighbors, family members, and enslaved workers all contributed to raising structures. The lack of professional architects or builders meant that most homes followed vernacular traditions, adapted from English rural models but modified for the Virginia climate and available resources. Over time, regional variations emerged, with German and Scots-Irish settlers in the Valley favoring log and stone construction, and English settlers in the Tidewater and Piedmont relying on timber and, for the wealthy, brick.

Defining Features of Colonial Virginia Architecture

Form Follows Function: Simplicity and Adaptation

Colonial Virginia homes were designed for practicality, not show. Their features reflect the needs of daily life, the limitations of materials, and the skills of their builders. The architecture of this period is often called “Post-Medieval English” or “First Period” in recognition of its roots in English vernacular traditions, but it quickly evolved to meet the realities of the New World.

Steeply Pitched Gable Roofs:

The steep gable roof was a hallmark of colonial homes. This design helped shed rain and snow, essential in Virginia’s variable climate. The simple triangular form was easy to construct with hand tools and local timber. In some cases, clapboard or thatch was used for roofing, and the steep pitch prevented water infiltration and rot.

Large Exterior-End or Central Chimneys

Early colonial houses often featured a large central chimney, which provided heat to multiple rooms and allowed for efficient use of firewood. The central location also helped retain warmth in winter. In later examples, especially as homes grew larger, end chimneys became more common. Chimneys were often built of brick or stone, even when the rest of the house was wood, as a fire safety measure.

Small, Multi-Paned Windows with Shutters

Glass was expensive and difficult to obtain, so windows were small and often consisted of multiple panes set in wooden frames. Shutters were functional, providing protection from storms and insulation in winter. The small size of windows also helped retain heat and reduce drafts. Early windows were often casement style, with leaded diamond panes, later replaced by sash windows as glass became more available.

Minimal Ornamentation

Colonial homes were plain and unadorned, with little in the way of decorative trim or moldings. This reflected both the settlers’ limited resources and their focus on survival. Any ornamentation was typically reserved for the most prominent members of the community or for public buildings. The lack of overhanging eaves or cornice detailing was typical, as these features required extra labor and materials.

One or One-and-a-Half Stories

Most colonial homes were modest in scale, with a single story or a loft under the roof. The hall-and-parlor plan, a large multipurpose room (hall) and a smaller private room (parlor), was common. As families grew or prospered, lean-tos or additional rooms were added to the original structure. The “I-house” form, two stories tall and one room deep, would become more common in the 18th century.

Clapboard, Log, or Brick Walls

Depending on the region and available resources, walls were constructed of hand-hewn logs, split clapboards, or wattle and daub. The exterior was sometimes whitewashed for weather protection and to reflect sunlight. In rare cases, brick was used for the entire structure, as at Bacon’s Castle, but most homes were wood.

Asymmetrical Facades and Off-Center Entrances

Early colonial houses often had slightly off-center entrances and asymmetrical facades, reflecting the practical realities of construction and the lack of formal design. Batten doors and small dormers were common.

Regional Variations and the Rise of the Plantation System

Tidewater Plantations and Vernacular Dwellings

The plantation system, based on tobacco cultivation and enslaved labor, shaped the landscape of Tidewater Virginia. Large plantations sprawled along the rivers, with the main house, outbuildings, and slave quarters forming self-sufficient communities. While a handful of brick mansions like Bacon’s Castle survive, most people, enslaved and free, lived in simple, perishable wooden dwellings. These homes were often one or two rooms, with dirt floors and minimal amenities.

Outbuildings and Community Structures

Colonial estates included a range of outbuildings: kitchens, smokehouses, dairies, barns, and slave quarters. These were typically built of wood or log, with the same practical features as the main house. Churches, courthouses, and taverns were also constructed in the colonial style, often with similar materials and forms.

Why So Few Colonial Examples Remain

Impermanence and the March of Time

Most colonial Virginia homes were built for short-term use, with little expectation of lasting more than a generation. The earthfast construction method, while expedient, left wooden posts vulnerable to rot, insects, and fire. As the colony prospered and the population stabilized, wealthier Virginians replaced their early homes with more permanent brick or frame houses in the Georgian style.

Natural disasters, neglect, and the relentless march of progress have erased most traces of the earliest colonial buildings. Today, what we know of these structures comes largely from archaeological excavations, written descriptions, and a handful of rare survivors.

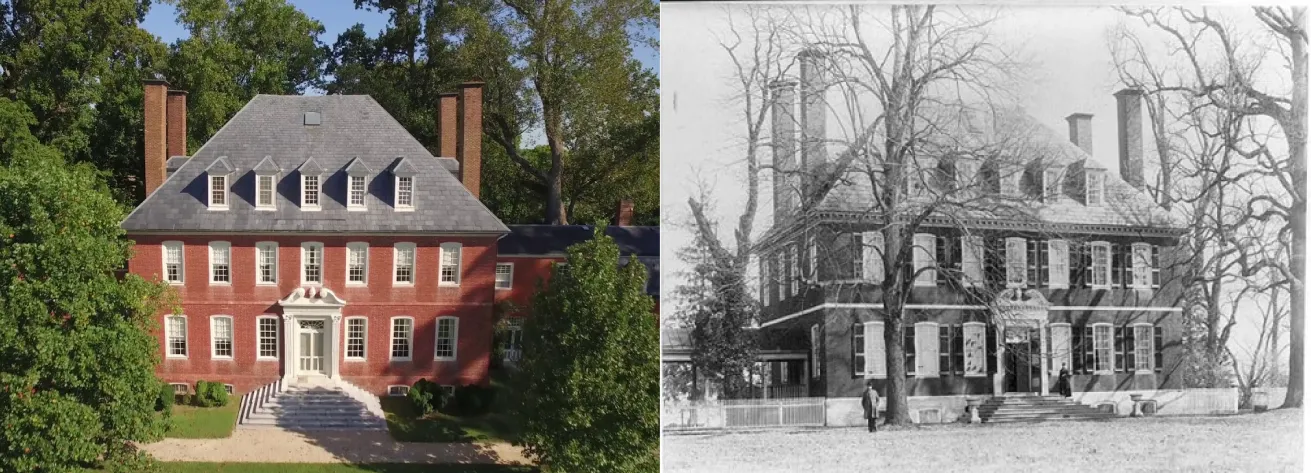

Surviving and Documented Examples

Few true colonial homes remain standing in Virginia. The Thoroughgood House (c. 1720) in Virginia Beach and Bacon’s Castle (1665) in Surry County are among the rare brick survivors, but even these are exceptional and not representative of the typical colonial dwelling. Most surviving evidence comes from archaeological sites, such as the remains of early Jamestown buildings, where post-hole patterns reveal the outlines of earthfast houses.

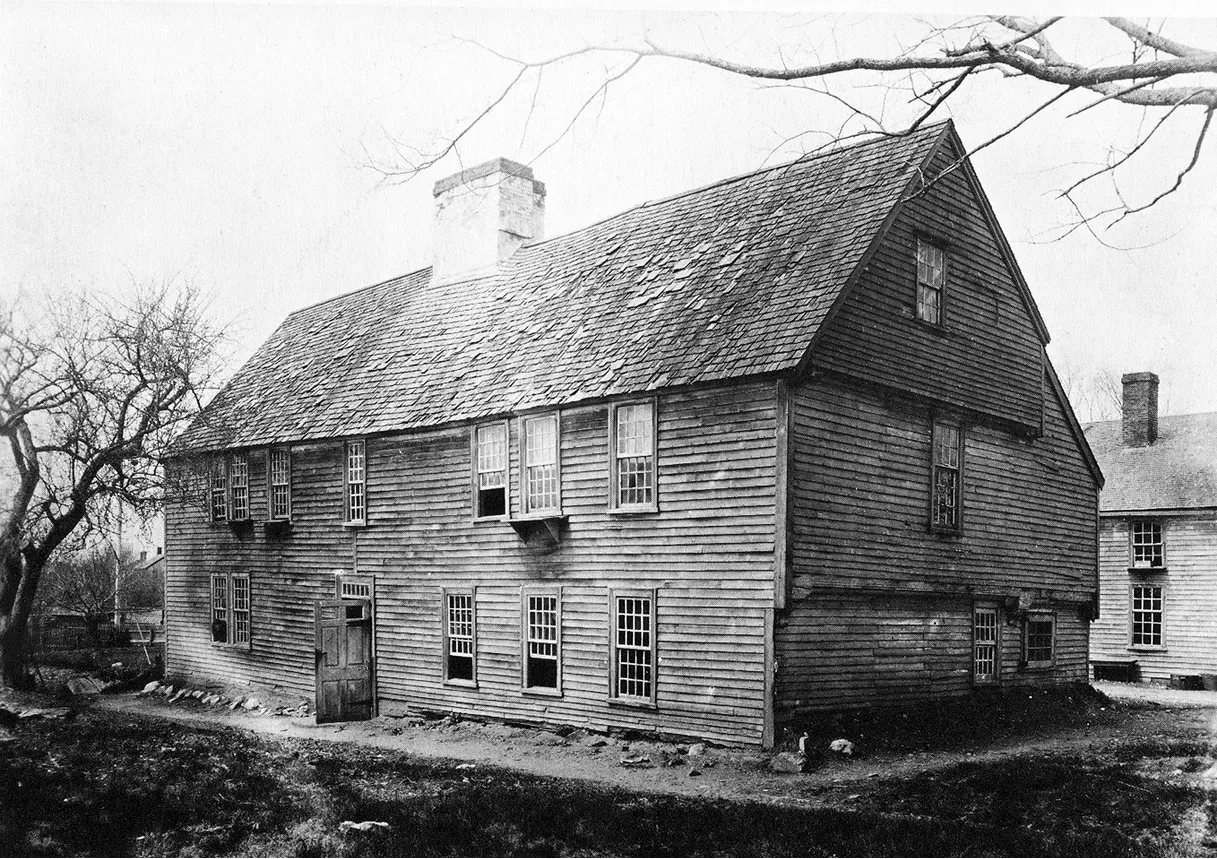

For a sense of what early colonial homes looked like, historians often turn to better-preserved examples in New England, such as the John Whipple House (Ipswich, Massachusetts, 1677), which shares many features with Virginia’s lost dwellings: steep gable roofs, central chimneys, small windows, and minimal ornamentation.

Legacy and Influence of Colonial Virginia Architecture

Setting the Stage for Later Styles

While few original colonial homes survive, the style’s influence endures. The practical, unpretentious forms of colonial architecture set the stage for the more refined Georgian and Federal styles that followed. The emphasis on local materials, adaptation to climate, and communal building traditions became hallmarks of Virginia’s architectural identity.

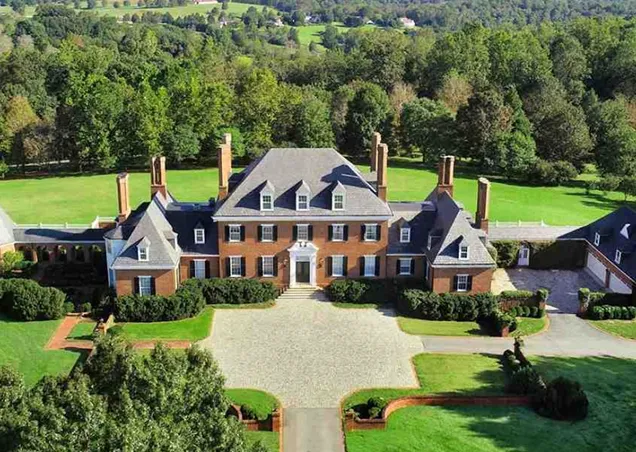

In the 20th century, the Colonial Revival movement drew inspiration from these early forms, reinterpreting their simplicity and functionality for modern homes and public buildings.

Building on Tradition: Colonial Architecture Today

Today, the spirit of colonial architecture lives on in Virginia’s rural landscapes, historic districts, and new homes designed to evoke the past. Whether restoring a rare survivor or building anew in the colonial tradition, understanding the motivations, materials, and methods of Virginia’s first settlers is essential to preserving the authenticity and character of this foundational style.

If you are considering restoring a historic home, building a new residence in the colonial tradition, or simply want to learn more about Virginia’s architectural heritage, Commonwealth Contractors offers unmatched expertise and a deep respect for the region’s history. Contact us today to discuss your project and discover how we can help you bring the enduring beauty of colonial architecture to life in your home.

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

%2520(1).webp)

%2520(1).webp)

%2520(1).webp)

.webp)

.webp)

%2520(1).webp)

%2520(1).webp)

%2520(1).webp)

%2520(2).webp)

%2520(1).webp)

%2520(2).webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

%2520(2).webp)

.webp)

.webp)

%2520(1).webp)

.webp)

%2520(3)%2520(1).webp)

.webp)

%2520(1)%2520(1).webp)

.webp)

%2520(1).webp)

%2520(2)%2520(1).webp)